Behind closed doors

New pentagon policy stamps out Press freedom

I was initially alarmed on behalf of journalists when I heard about the new policy at the Pentagon.

The policy demanded journalists sign what amounted to a pledge that even unclassified information would first be cleared by the military before the press was able to release it. I have been keeping track of how this policy has been changing the face of defense reporting in the past few weeks. And already I have witnessed reporters change their positions, stories be postponed or edited, and transparency suffer. What does this imply of the news that we watch, what the people know, and of democracy?

The policy that made everything different

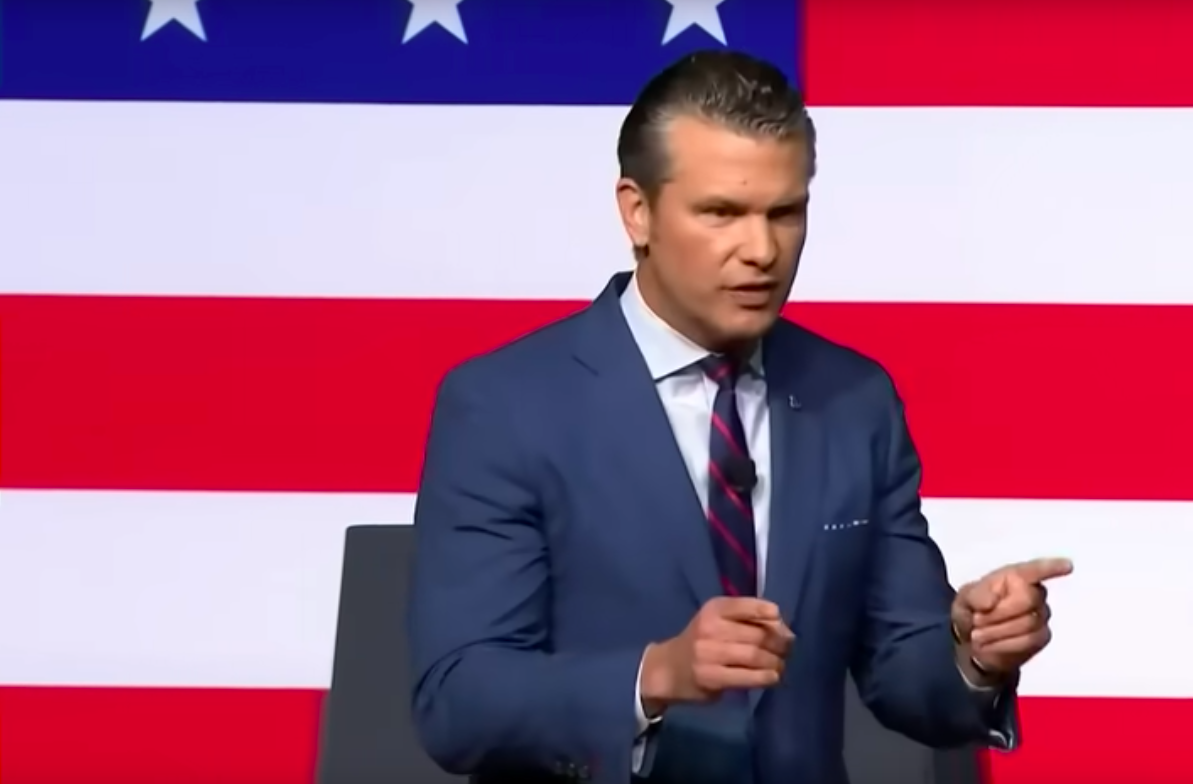

In mid-September 2025, Secretary Pete Hegseth of the recently rebranded Department of Ward made a policy that is mandatory: any credentialed journalist must sign a pledge that any information that the Department releases must be formally cleared before any release—even that which is not classified. Journalists who do not comply will be denied press credentials or access to all areas of the Pentagon.

In addition to that, other limitations include escorts for reporters in some areas previously not required and the inability to move freely in some parts of the building that were previously open as press corridors, as well as prohibiting access without following some conditions. This memo is approximately 17 pages long, which covers new credentialing and behavior requirements.

The most surprising thing to me is the broad sweep of it: not only of what reporters are allowed to publish, but of what they are able to see, ask, and notice.

Reporters shift their coverage

I had virtual conversations with several journalists who report on the Pentagon to understand how the policy has already brought about changes. They are not named here to protect their reporting, employment, and First Amendment rights of freedom of the press despite the new policy.

One reporter indicated they no longer would use anonymous sources within the Pentagon unless they are already cleared some steps with the public affairs offices, or they think there will be delays in their publication. Stories that used to be posted fast following press briefings are now in limbo as reporters wait to be approved.

Others responded that they changed headlines and deleted what could have been potentially controversial information that could be deemed as controlled unclassified information so that they could not push the limits of what the Pentagon would not accept or could even get access to.

Others too have started to restrict off-the-record conversations; when reporters used to have little informal walks down the corridors and picked up what they could overhear in a chat, now everything is curated, planned, and meditated.

The implication of these changes is chilling: it is not in every case that there is outright censorship, but that such effects are widespread enough that reporters are censoring themselves or withholding stories that they might otherwise have posted.

The implications of this on audience and public understanding

These changes have practical effects on the masses.

It delays reporting, meaning less robust and slower news.

When the information has to come through the gates, time is lost. It implies less immediacy, fewer whistleblower tales, and fewer revelations of what is going on in the Pentagon. This leaves the audience with what the Pentagon desires to be publicized, which is not necessarily what is needed in order to hold them accountable.

There’s less depth of investigation.

Articles that used to delve into how choices were being made within the defense machine now look at what was officially allowed. That holds back critical journalism. As an example, information concerning the internal policy difference of view or leakage that can be used to expose citizens to debate can be lost or diluted.

Trust is eroded.

When the audience finds out that the press must concur on the guidelines of reporting, there is loss of trust in journalists. Is that to say that what is being reported is filtered? Is the narrative being formed by the government? Those are tough questions that people will pose, and answers might never be transparent without being disclosed.

There’s a lack of transparency in what’s reported.

This policy creates a wall between the knowledge accessible to the people — particularly in a democracy — and the knowledge accessible to the government. When it requires reporting to be sanctioned prior to publication, then access is conditional. Not only is transparency no longer automatic, but it will be conditional based on adherence to official standards — which may change over time, and these changes are often secret.

How this stacks up globally

Let’s compare the way other democracies manage the access to the defense institutions; the difference is significant.

In the U.K. there are protocols on sensitive information and occasional seals on the name of national security, but no blanket oaths on unclassified information to be signed by journalists. The vibrant tradition of strong leaks, autonomous examination, and judicial appeal exists.

In France and Japan, the same rules are followed: unclassified information can be published without the previous consent, but with a responsibility to source and verify it. The competition in courts can be healthy sometimes in terms of matters of public interest.

Relatively, the U.S. policy seems stricter in formalizing pre-approval conditions, which puts pressure on the reporters who are willing to report on the defense matters on their conditions.

Legal and moral imperatives: What’s constitutional about this?

The First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press, but what are the new regulations doing in reference to the already constituted law?

Most organizations, including the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, noted that requiring access on the condition of signing an agreement not to publish some unclassified information constitutes a prior restraint, which is usually not well received in the constitutional law of the United States.

According to legal commentators I have consulted, in cases where reporters are under threat of having credentials suspended, it is not just a regulation but rather a punishment of future speech. That casts grave First Amendment concerns.

Also, the so-called Pentagon pledge is also under scrutiny not only on what is forbidden but also on the meaning of what is meant by controlled unclassified information. It is a legally gray category, which gives much discretion to the government officials.

The current impact of the policy on the news output

Such sources of news as The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Reuters have released statements to criticize the policy and are considering how to either comply or go on the offensive.

There are delays or less detail in some of the stories that previously emerged out of Pentagon briefings—particularly those based on background interviews or unofficial sources. Indicatively, an exposed chat on military operations reported on one occasion led to embarrassment for the leadership at the Pentagon. Subsequently, sources mention that it became more limited in briefing content and informal gatherings.

The reporting tone has changed to become more cautious. Reporters I have been talking to said that they are staying off of anything that may go wrong with approval clauses, even at the cost of making the people less transparent.

What do I find here?

As a foreign correspondent, I have always considered the United States to be an international champion of freedom of speech — a country where journalism had the right to express its views and facts without fear of reprisal. But policies like this new Pentagon directive are the exact opposite of that reality and ideal. The very country that teaches the world lessons in transparency and accountability is itself imposing restrictions that the United States would criticize if implemented in any other country.

This is not an isolated incident. The designation of non-classified information as controlled unclassified information,

the prosecution of whistleblowers under the Espionage Act, and the surveillance of journalists’ conversations and communications all demonstrate that the grip on knowledge and information is becoming increasingly tight. The trend is clear: investigative journalists who expose national security concerns fear consequences that will be imposed on them, and that fear is growing by the day.

This decline is both startling and instructive for countries like ours. When a country long considered the home of the First Amendment begins to clamp down on its own journalists, what message does it send to governments that already have little tolerance for dissent? America’s strength has always been in its freedom of press; if the same country now closes its doors in the name of control, it will undermine not only its journalism but also its moral high ground.

I believe in the fundamental principle of journalism that where there is darkness, there is light — especially when we report on the Pentagon. This new policy threatens to turn transparency into a license; journalists will now have to wait for government approval before releasing information that is actually classified.

This is not just a change in the administrative structure, but a change in what gets to the public and who gets to decide. And that is the point that journalism’s watchdog role is most responsible for protection.

Ishraq Ahmed Hashmi is a freelance journalist and commentator who concentrates on accessibility, media ethics and social justice. His work discusses the way in which inclusive practices can transform journalism and open up the engagement of people. Follow him on LinkedIn at /in/Ishraq-Ahmed-Hashmi.

This is analysis. It looks at a situation or trend through facts, figures, public reactions, and expert response.

Want more of the Word?

Become a Word Patron

Love what you’re reading? Want a to read more? Become a Patron and support The Word for as little as $2.99 a month.